We held the final AGM for the Marine Biosecurity Toolbox project, after five years of intensive research and collaborations.

Teaming-up with the Five Million: Exploring motivation of Kiwis to participate in the detection of marine pests

The DETECT component of the Marine Biosecurity Toolbox programme aims to engage with the team of five million New Zealanders and empower citizen-driven marine biosecurity surveillance for detecting marine non-native invasive species. To get a glimpse of citizens’ attitudes towards biosecurity in the marine environment and marine pest detection activities, Dr Richard Yao (Scion) led a focus group in November 2020, in collaboration with Drs Xavier Pochon, Anastasija Zaiko (Cawthron), Jo Stanton (University of Otago), Melissa Welsh (Scion) and in coordination with the programme’s partner teachers Natalie Tredidga (Nelson College for Girls) and Johnnie Fraser (Nelson College). The focus group was hosted at Nelson College for Girls and consisted of a mix of adults and senior students (Year 12-13).

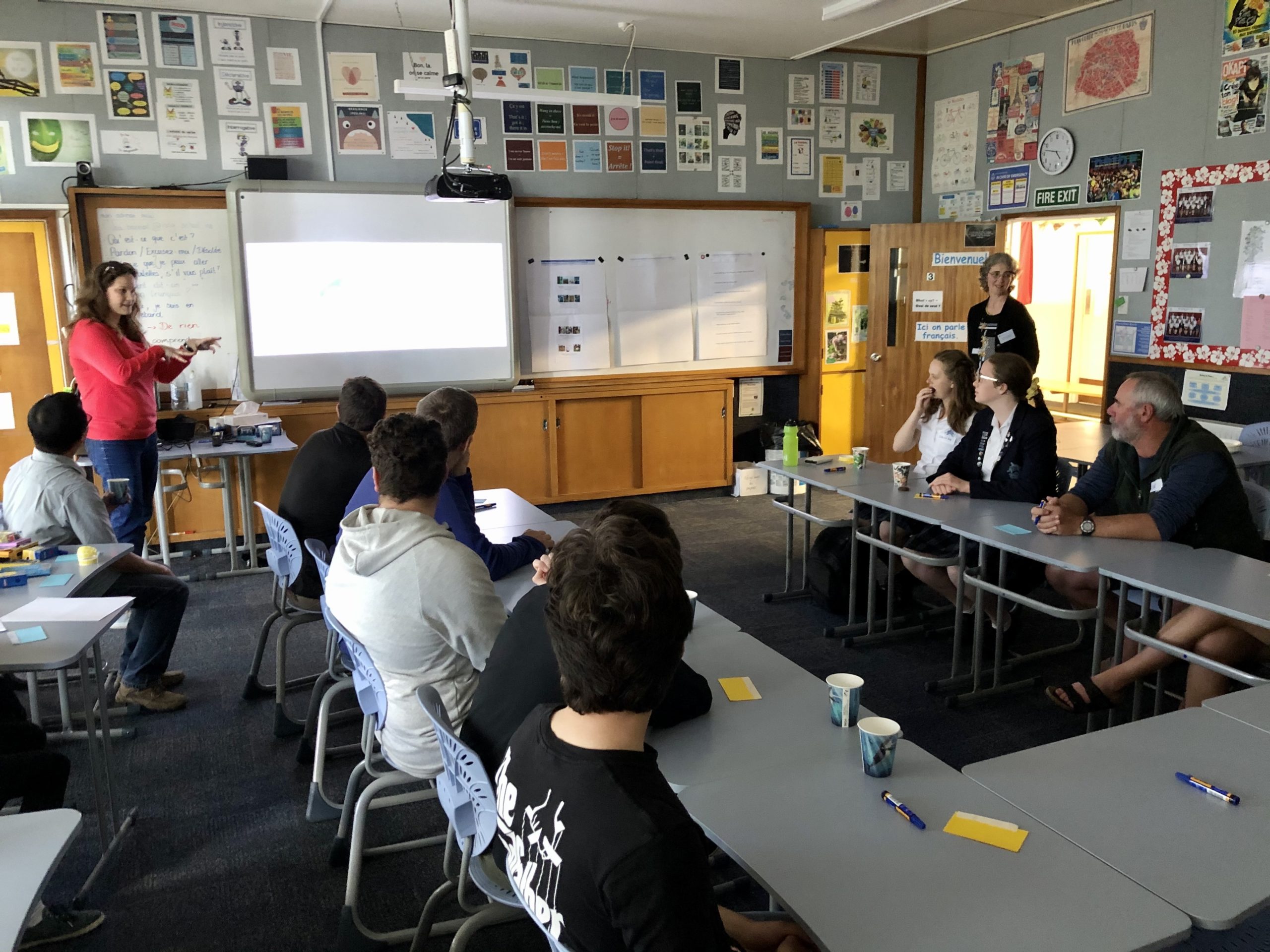

The objective of the focus group was to find out if the public would be willing to participate in detection activities, what types of detection activities are appealing and what would drive their participation. The research team developed the focus group design which has been reviewed and approved by Cawthron’s ethics approval committee. The evening started with a presentation giving an overview of the marine biosecurity issues in New Zealand and worldwide, importance of surveillance programmes and public engagement (Figure 1). This was followed by nine focus group questions. Materials such as flip charts, Post-it notes, pens, and sticky dots were organised to gather responses. Snacks and drinks were also provided helping to make the evening an enjoyable experience.

Figure 1. Anastasija Zaiko (Cawthron) presenting an overview of the marine biosecurity surveillance concept and approaches to the focus group participants.

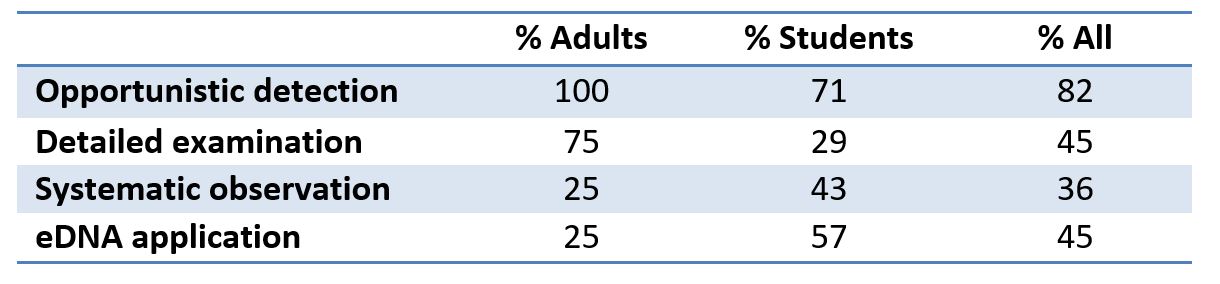

Participants were presented with four detection approaches starting with the less involved ‘opportunistic visual detection’; followed by ‘detailed examination’ (e.g. employing microscopes) and ‘systematic observation’ approaches; and then – using the novel ‘eDNA detection tools’. They were then asked to place a sticky dot next to the approaches they would consider being involved with. Opportunistic detection was chosen by 82% of the participants (Table 1). It is interesting that while the eDNA application was considered by the lowest proportion (25%) of adults, it was the second most preferred option (57%) for students.

Table 1. Ranking of preferred detection approaches by focus group participants.

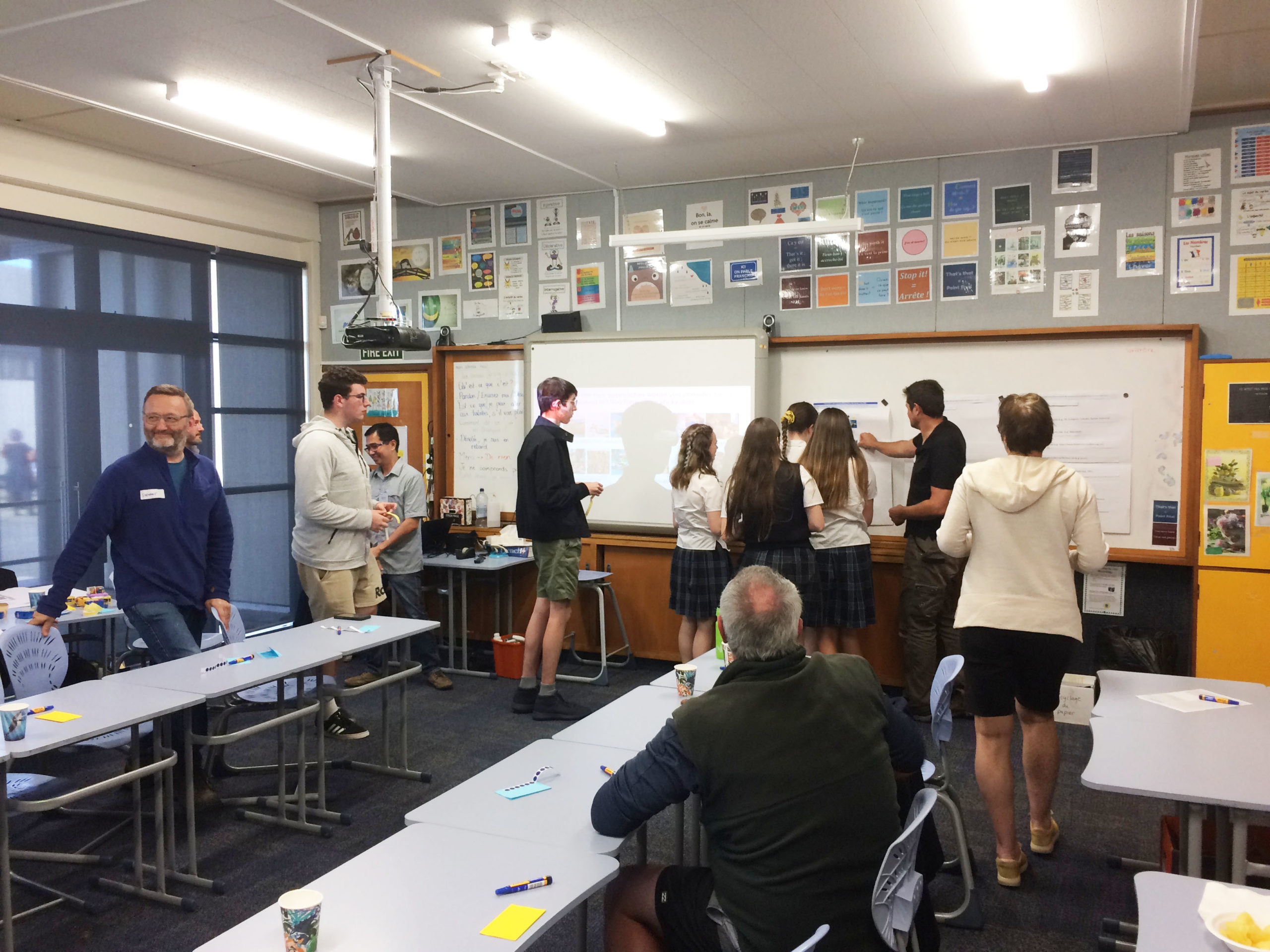

To gain further insight, each participant was asked to write on Post-it notes why they would choose to participate in a marine pest detection initiative. They were then asked to vote on each other’s ideas using sticky dots (Figure 2). Questions were also asked regarding how participants would prefer to interact with biosecurity researchers and each other, at what times of the year and what types of incentives or rewards might encourage involvement.

Figure 2. Participants respond to questions by placing sticky dots next to options listed on a flip chart.

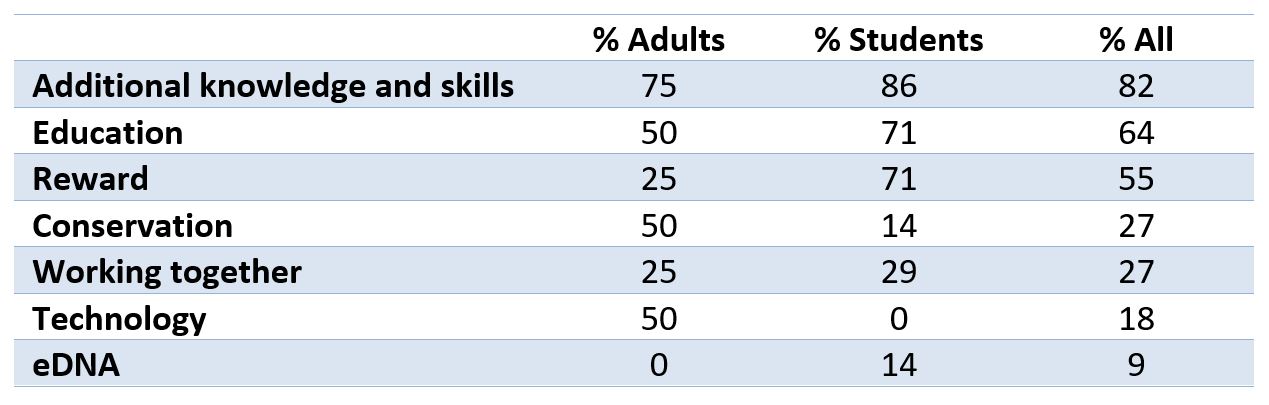

Each participant was asked to provide a maximum of three factors that would likely encourage participation in a marine pest detection initiative. In total, 28 factors were provided, and these were grouped by the facilitators into seven categories: Additional knowledge and skills, Education, Reward, Conservation, Working together, Technology and eDNA. Each participant was then asked to vote for a maximum of three most appealing factors using sticky dots. ‘Additional knowledge and skills’ was voted by the highest proportions of adults (75%) and students (86%). ‘Reward’ seems to be more attractive for a greater proportion of students (71%) than adults (50%). While ‘Conservation’ and ‘Technology’ were more important drivers for adults (50% each) than for students (14% and 0%, respectively).

Participants were also presented a list of platforms that can be used for reporting the results of potential marine pest detection activities. They were then asked to vote for their three most preferred platforms using sticky dots. The greatest majority of adults (75%) and students (86%) voted for smartphone apps (Table 2). The largest proportion of students also voted for social media while a slightly lower proportion of adults (50%) voted for it. Website was preferred by the largest proportion of adults (75%) while it appealed less for students (14%). Consequently, no participant voted for the conference call platform while only one student voted for a formal event (e.g. conference).

Table 2. Preferred platforms for reporting the results of potential detection activities.

In terms of the preferred season for marine pest detection, all adult participants voted for both summer and spring, while all students voted for summer only. About half of adults and students would participate in autumn while a quarter of both groups would join winter marine detection activities. Finally, participants were asked if they would consider joining a follow-up focus group. All eleven participants indicated they would. This suggests a positive, enjoyable experience, and good engagement with the topic.

Overall, the evening was a great success, resulting in a set of useful baseline data and inspiring feedback from the participants. From this, the team will develop further focus groups and surveys that ask the right questions about citizen science and community engagement in New Zealand marine biosecurity initiatives.

Comments (0)